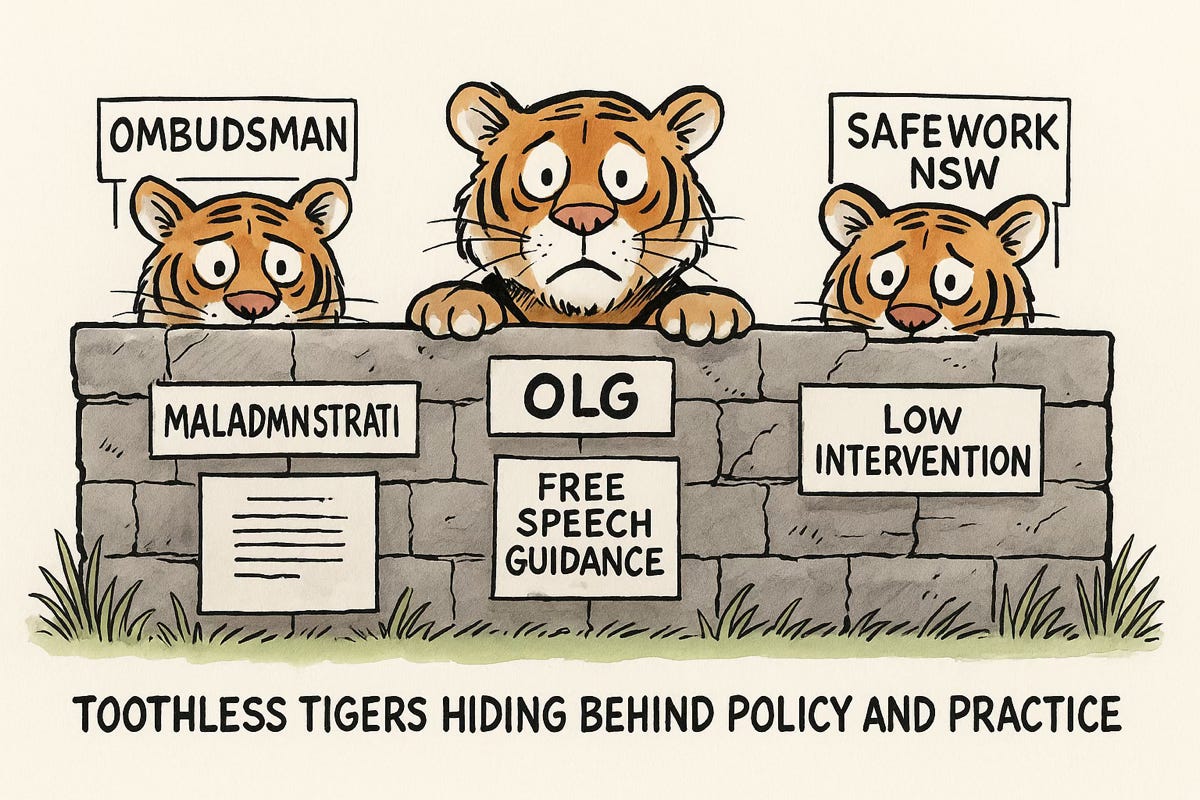

One of the most pressing questions facing residents in NSW is not just why local councils tolerate poor behaviour in their chambers, but why the state regulators—those tasked with oversight—seem unwilling to intervene.

The problem is no longer about isolated incidents of misconduct; it is about a systemic reluctance to address conduct that erodes trust, destabilises governance, and creates unsafe workplaces.

The “Free Speech” Shield

The Office of Local Government (OLG) recently issued guidance on Free Speech in Local Government. On its face, the guidance has a laudable intent: to protect robust debate and ensure councillors can express strong political views without fear of sanction.

But in practice, it has become a shield for poor behaviour.

The document explicitly advises that most disputes about behaviour in meetings should be dealt with at the time, by the Chair, rather than through Code of Conduct complaints afterwards. Only behaviour deemed “particularly egregious” is suggested to warrant post-meeting complaint processes.

The Moving Target of “Particularly Egregious”

The OLG guidance says that only behaviour that is “particularly egregious” should be dealt with after the meeting through the Code of Conduct. But what does that mean in practice?

The bar is set so high that most complaints will be dismissed as routine debate. Unless a councillor threatens violence, uses discriminatory slurs, or makes explicit allegations of corruption against named individuals, regulators will say the matter should have been handled during the meeting. In other words, shouting, bullying, intimidation, or repeated hostile commentary—behaviour that in any normal workplace would trigger an HR or WHS investigation—may be excused under the umbrella of “free speech.”

This selective standard leaves councillors and staff vulnerable and gives disruptive actors more room to push boundaries without consequence.

The Ombudsman’s Limited Role

The NSW Ombudsman is another body residents turn to when councils go wrong.

But the Ombudsman is bound by legislation to focus on maladministration, not personal behaviour. Its remit is about whether processes are lawful and fair, not whether councillors are shouting, intimidating staff, or running factional caucuses behind closed doors.

Even when issues are raised, the Ombudsman frequently declines to act on the grounds that complaints relate to discretionary decisions by councils, or that internal remedies (such as the Code of Conduct) have not been exhausted. Again, the effect is delay, deferral, and inaction.

ICAC’s High Threshold

The Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) only steps in where there is evidence of corrupt conduct—defined narrowly as deliberate dishonesty for personal gain or improper advantage. This sets a very high threshold.

Council dysfunction—bullying in the chamber, political factionalism, undermining of staff—rarely meets ICAC’s test.

The result is that residents who expect ICAC to be a “watchdog” are told that while behaviour may be concerning, it does not rise to the level of corruption.

SafeWork and WHS Oversight

Workplace health and safety law should, in theory, offer a clearer avenue.

The WHS Act 2011 (NSW) imposes duties on councils (as PCBUs), on mayors and CEOs (as officers), and on councillors (as workers) to ensure that the council chamber is a safe workplace, including psychologically safe. Bullying and harassment are explicitly recognised as hazards.

Yet, SafeWork NSW often adopts a low intervention model. Unless the risk is extreme, sustained, or clearly documented, complaints are triaged out, with advice to resolve the issue internally.

This mirrors the OLG’s approach—pushing matters back into the very organisations that are failing to manage them.

Why the Reluctance?

Several patterns explain why regulators collectively avoid acting:

Fear of politicisation: Regulators are wary of being seen to intervene in political debate, so they default to inaction.

Resource constraints: Each regulator has limited investigative capacity, and Code of Conduct disputes are treated as “low priority” compared to corruption or serious safety breaches.

Legislative silos: OLG handles governance, SafeWork handles safety, Ombudsman handles maladministration, ICAC handles corruption. Behavioural issues in chambers fall between these silos—serious enough to harm governance, but not neatly within any one agency’s jurisdiction.

Reliance on “self-regulation”: The system assumes councils will correct themselves through Codes of Meeting Practice and internal complaints systems. In practice, factional majorities use this discretion to shield themselves.

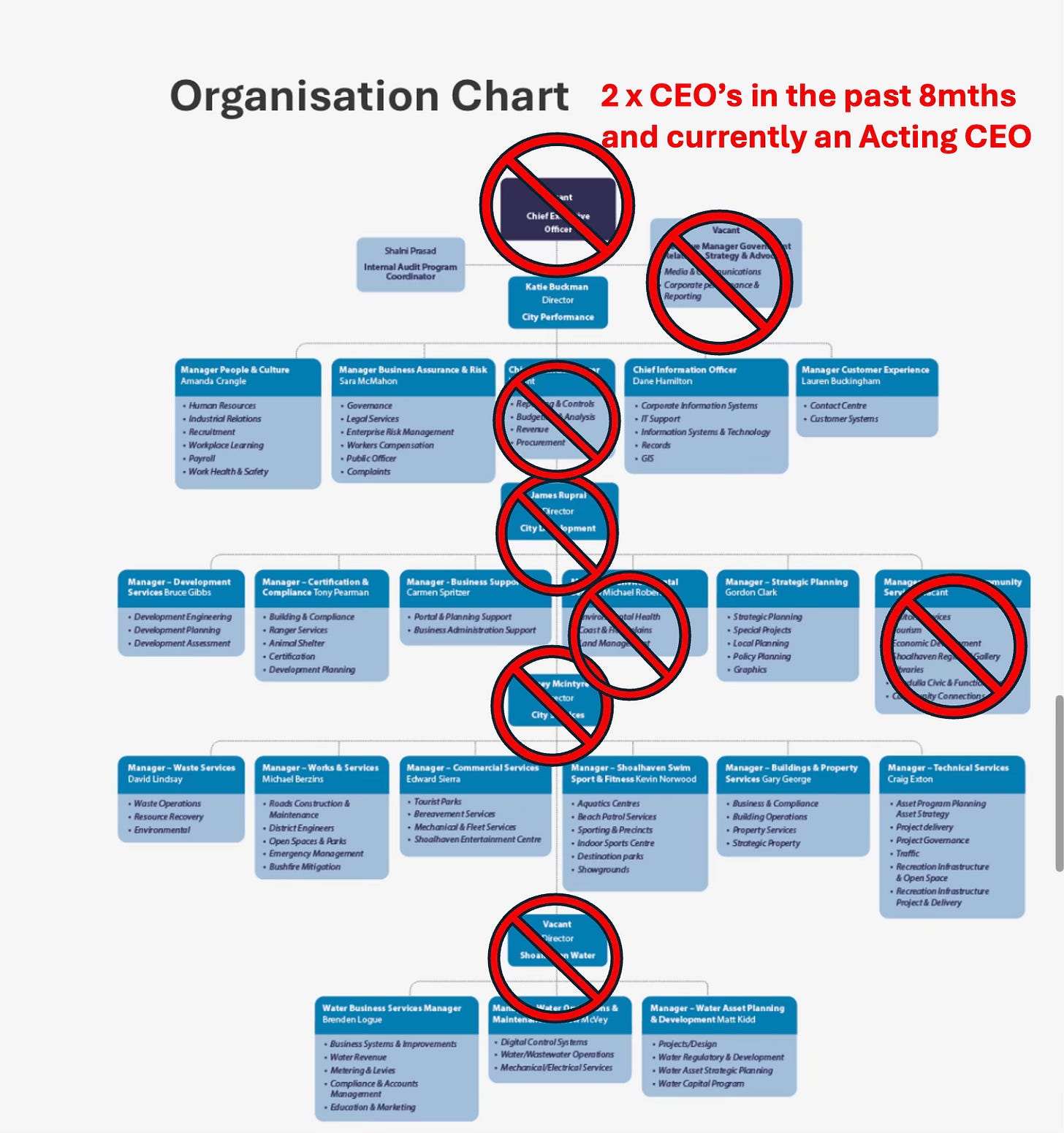

Well that is working out well here in the Shoalhaven - CEO number 3 in one year and look at the org chart - yep a model of well run local government :).

The Result: A Governance Vacuum

The consequence is clear: there is a governance vacuum. Councillors who shout down their colleagues, cast baseless accusations, or intimidate staff know that state regulators will not act.

The message is that as long as conduct falls short of outright corruption or criminality, it is tolerated.

For residents, this erodes trust. For staff, it creates a psychologically unsafe workplace. And for councillors who seek fairness and integrity, it is demoralising—knowing that complaints will be dismissed as not “egregious” enough, not “corrupt” enough, or not “maladministration” enough.

What Needs to Change

Lower the intervention threshold: Behaviour that creates unsafe or hostile environments should trigger regulator attention, not be excused as “just debate.”

Clarify WHS obligations for councils: SafeWork NSW must treat chambers as workplaces and hold mayors and CEOs accountable for psychosocial risks.

Integrate oversight: A joint protocol between OLG, Ombudsman, SafeWork, and ICAC could ensure that bad behaviour doesn’t fall through the cracks.

Empower residents: Members of the public should have clearer, simpler pathways to escalate concerns when councils fail to regulate themselves.

Conclusion

It appears state regulators do not want to act on bad behaviour in councils because the system is designed to avoid intervention. The OLG narrows accountability under the guise of free speech. The Ombudsman defers to councils. ICAC sets the bar impossibly high. SafeWork often triages complaints away.

The result is that dysfunction festers, reputations suffer, and the public is left to wonder: if the watchdogs won’t bark, who will keep our councils in line?

State regulators will not change their approach unless there is political pressure.

That’s why it is vital for residents to raise these concerns directly with their local Member of Parliament and with the NSW Minister for Local Government.

MPs and ministers MAY respond when constituents highlight that dysfunction in councils is not just “local politics,” but a matter of workplace safety, public trust, and accountability.

By writing to them, you send a clear message that the community expects better oversight and reform of a system that currently excuses bad behaviour under the banner of “free speech.”

Template Message – Local MP

Subject: Concern about Shoalhaven Council Conduct and Oversight

Dear [Local MP’s Name],

I am writing as a constituent to raise my concerns about the dysfunction and hostile behaviour in Shoalhaven City Council meetings, and the lack of meaningful intervention by state regulators.

The council chamber is a workplace. Under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (NSW), councillors, staff, and members of the public are entitled to a safe environment, free from bullying and intimidation. Yet, regulators frequently dismiss complaints on technicalities, citing “free speech” or thresholds that are too high to protect anyone in practice.

I ask that you raise this matter with the NSW Minister for Local Government and support reforms to ensure that councils are properly held accountable. Residents deserve confidence that when behaviour in the chamber becomes unsafe, regulators will act.

Sincerely,

[Your Name]

[Your Address]

Template Message – NSW Minister for Local Government

Subject: Request for Action on Behaviour and Oversight in Local Councils

Dear Minister,

I wish to draw your attention to the ongoing dysfunction and hostile behaviour in Shoalhaven City Council meetings. Behaviour that would not be tolerated in any normal workplace is excused in the chamber under “free speech” guidelines, leaving councillors and staff exposed to bullying, intimidation, and psychological harm.

The Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (NSW) makes it clear that council chambers are workplaces, and yet neither OLG, SafeWork NSW, nor other regulators appear willing to intervene when standards are breached. This leaves residents without protection and erodes public confidence in local government.

I urge you to take action to review the current regulatory framework and provide clearer, stronger pathways for intervention when councils fail to maintain safe and respectful workplaces.

Yours sincerely,

[Your Name]

[Your Address]

Please share this with 2 friends who care about Shoalhaven.

If you get value from this post and you want to help me with information applications to get to the bottom of issues, you can donate here.

Thank you for considering this, the posts will always be free - but I could do with some help :)

Here are the current applications to council, seeking documents. At the moment I have one matter before NCAT. I will fight for transparency.

Disclaimer: This article provides analysis and commentary based on publicly available information and council transcripts. It does not make allegations of misconduct by any individual. Readers should verify details independently before drawing conclusions.

Here is a quick disclaimer, or explainer on the use of AI in the Eye.

Competence and consistency are not big in OLG…